Between October 2019 and June 2020 women lost jobs at a greater rate than men, while the employment recovery rate in the third quarter of 2020 was slightly higher for men, widening the gender gap. These are some of the key takeaways of BBVA Research’s 'Gender diversity and training' paper. According to the report, published on the occasion of BBVA’s diversity workshop (Diversity Days), training is one of the essential factors to reversing this situation and boosting women’s participation in the digital economy, a sector that’s recovering at a faster pace.

The COVID-19 pandemic is taking a high toll on Spain’s economy in terms of production and employment. According to data published by the Spanish Statistics Institute (INE), the economic downturn translated into a job loss rate of 18.5 percent in the second quarter of 2020 (compared to the second quarter of 2019) and 5.7 percent in the third quarter of 2020 (compared to the third quarter of 2019). Breaking down this data by gender, there are differences in this decline between men and women.

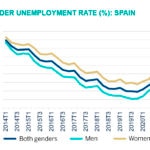

The previous economic crisis reduced gender differences in the unemployment rate (which stood at nearly 27 percent in early 2013). The recovery that followed that crisis caused unemployment rates to drop, albeit differently for men and women (leaving the unemployment rate for women above the rate for men), thus widening the employment gender gap. According to the data resulting from the first impact of COVID-19, there’s been a slight increasing trend in gender differences of the unemployment rate.

Source: INE, EPA

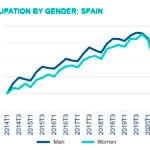

Taking employment data as a reference, in the months leading to the pandemic employment grew at a slighter higher rate among men than among women. “COVID-19 caused a dramatic drop in employment figures in the first half of 2020, and a steeper one for women than for men,” explained Alfonso Arellano, author of the study. According to BBVA Research’s economist "the employment recovery experienced between the second and third quarters of 2020 was relatively better for men than for women,” widening the gender gap.

Distribution of female employment by economic sector

In terms of employment, the impact of the pandemic varies significantly across industries. The previous economic crisis (which affected certain sectors – such as the construction industry - particularly had) contributed to narrowing the gender unemployment gap. Employment rates in some sectors, such as the financial and insurance industries or Public Administrations, are more resilient compared to other fields of activity, such as the arts, or services like trade, transport and hospitality.

“Four sectors account for over 50 percent of female jobs: commerce, hospitality, education, and healthcare and social services, which were directly involved in the impact of the pandemic,” says Arellano. Although for the time being COVID-19 maintains the representativeness of men and women in the sectors as a whole, a composition effect can be observed in employed women, who have seen their weight decline in the hospitality industry while it has risen in the field of healthcare and social services. Furthermore, the worst performing sectors in terms of employment are the ones where women’s participation has increased the most (except in the case of hospitality).

Source: INE, EPA

In this sense, education has a huge impact on opportunities to land and keep a job, and it contributes to reducing the representativeness differences between population and occupation. Education is more important for women: in higher education tiers, gender differences in unemployment rates decline. “This indicates that education becomes a defining element for workers, especially for women,” says the economist. The gender gap in the illiterate group is 19.55 percentage points. In higher education groups, this difference dropws to 1.2 percentage points.

Digital economy and gender diversity

Focusing on digital-intensive sectors, on average, women are less represented in the digital economy compared to the whole of Spain (42.7 percent vs 46.3 percent), with significant disparities between activities. The digital economy performed slightly better during COVID-19 than the average for Spain, especially in activities related to services. Prior to the pandemic (INE, 2019), these sectors accounted for more than 17 percent of Spain’s gross added value, and about 17 percent of total employment.

Broadly speaking, the prevalence of permanent contracts is also higher across digital industries and female employees holding higher education degrees are also more likely to have a permanent contract in these sectors. The interest in increasing the presence of women in traditionally male-dominated fields of knowledge (such as in the so-called STEM careers) will be more sustainable in as far as this interest fits with the needs expressed by companies.

In addition to training, the study notes the possibility of improving gender diversity in the job market beyond knowledge. These training needs are a core element within the requirements of companies in their job offerings, but not the only ones. Other requirements that are becoming increasingly relevant include factors such as the development of abilities, skills or ways of working, the so-called 'soft skills'.

According to OECD data, while in Spain as a whole, companies demand by intensity a mixed range of factors between these four areas (training, skills, abilities and ways of working), in the case of companies in the digital economy, there is a clear predominance of ways of working, with the exception of administrative activities and support services, where knowledge-related factors predominates. Among the most demanded skills within the ways of working are awareness, achievement orientation, adaptability and independence.

Therefore, the report concludes that a higher training and educational background allows boosting resilience and improving an individual’s employment prospects, even during the pandemic. A more relevant conclusion in the case of women when it comes to reducing gender differences in employment. Improving other education-related factors, such as skills, abilities and ways of working can be a powerful tool to cope with the impact of COVID-19 on employment.