"Innovation: making a virtue out of necesity"

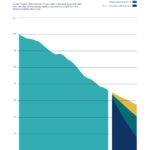

A simple accounting identity shows that greenhouse gas emissions that build up in the atmosphere and cause climate change evolve according to GDP and emissions intensity per unit of GDP. Global GDP grew by 114% between 2000 and 2022, while emissions intensity fell by 33%.

Assuming a trend economic growth of 3%, the current rate of improvement in intensity (1.8% per year on average) makes it impossible to achieve one of the objectives of the Paris Agreement: to limit the global temperature increase to well below 2 °C compared to pre-industrial levels, and to make efforts not to exceed 1.5 °C. In other words, net emissions should be zero by the middle of this century.

We need to reduce the energy intensity ratio and innovate if we hope to make a meaningful leap forward in the emissions trend and put their path on a trajectory consistent with net zero. This is particularly important when we consider that climate policies that seek economic degrowth to reduce emissions are impracticable due to their negative impact on the population’s welfare.

Climate change mitigation policies, while exceptionally diverse in the instruments they rely on, essentially pursue the same goal: to make emissions into the atmosphere more expensive to encourage the transformations needed to ensure that production and consumption do not ultimately resort to them. An example of how to make a virtue out of necessity is the oil crisis that took place in the 1970s: the increase in the price of oil and the very real threat of rationing, in addition to making oil drilling profitable in latitudes geopolitically more stable than the Middle East, led to tighter efficiency standards for combustion engines in transportation or increased innovation and greater investment in both nuclear power and renewable energy. All in all, according to World Bank data, the intensity of oil use per unit of GDP fell from 0.12 tons of oil equivalent back in 1970 to 0.05 in 2022, equivalent to a 58% decline Similarly, decarbonization requires innovation, spurred not only by geopolitics and the advantages of having a secure energy supply (as is currently the case), but also by the costs of climate change internalized within economic flows. We also have the sheer price-competitiveness gains provided by certain renewable energy sources that are already cheaper than fossil fuels for power generation. An improvement in the relative prices of renewable energy, once they become consolidated, would lead to further incentives to continue innovating and moving away from fossil energy sources.

Available empirical analysis shows that, in general, countries with more climate policies in place file more patents for innovations aimed at mitigating climate change or receive more “green” foreign direct investment, which may, in turn, boost economic growth in the medium-term. That innovation will eventually lead to more activity is not a given. Europe shares leadership with the United States and China in basic science research, the first stage of innovation, yet in the US marketplace advances end up becoming products in a more pronounce way. Europe is shackled by its below-par private risk financing mechanisms, and public financing also has room for improvement in adapting to the needs of different stages of project maturity to attract more private funding. Notably, the recent Draghi report points to various levers for increasing the financing of public goods, such as innovation, where the gap with the United States goes to the heart of the problem of Europe’s low productivity. Aside from the need to increase public financial capacity via a safe asset issued by the European Union, we would also do well to end the fragmentation of European capital markets by completing the Capital Markets Union while at the same time reforming the financial securitization market or extending the mandate of the European Investment Bank (EIB) to collaborate with venture capital initiatives.

It will not be the lack of proposals that will prevent us from making a virtue out of the need to respond to the climate crisis as we look to achieve a meaningful increase in socially and environmentally sustainable welfare.