Scientists say the next AI stage is near. Economists disagree. Here's why.

If you ask scientists in the field of artificial intelligence when they expect fiction to become reality and robots’ intelligence to exceed that of humans, they would likely say it’s right around the corner, sometime between 2030 and 2050.

But ask an economist and you’ll get a different answer.

Economists would tell you that even with the strides that have already been made in artificial intelligence, there have been no corresponding gains in productivity and no evidence that there’s going to be a fast integration of machines into our economic system. In fact, macroeconomic models conclude that it’ll be at least another 100 years before we reach the point where machine can best man.

Automation and digitization are penetrating the domain of truly human tasks such as reasoning and sensing, however, reviving the fear that new technologies will displace workers and give rise to technological unemployment. I say “revive” because the concern over such a threat is not new. A similar concern in the 1950s and 1960s led to the establishment of a national blue-ribbon commission to study the issue. One factor that differs now is that despite the rapid growth in information communication technologies, digitization, machine learning and mobile robotics, economists are puzzled by a couple of things -- consistently low productivity growth, meaning these machines aren’t making us more productive; and strong payroll growth and a historically low unemployment rate, meaning these machines aren’t putting people out of work, either.

No doubt there are some incredible machines around us already. We can easily purchase a drone with a camera, and there are even machines that work in hotels as room-delivery service robots. They independently navigate the hotel to deliver orders. This is very advanced because while machines can be programmed to do complicated computations, it’s actually very hard for them to do things that come easily to humans -- walking up the stairs without bumping into people, for instance, orienting themselves, holding a mug rightside up instead of upside down. Those aren’t exactly skills we’d put on our resumes, but turns out they’ll come in very handy in the supposed race with the machines.

While machines can be programmed to do complicated computations, it’s actually very hard for them to do things that come easily to humans

But even with that huge advantage, the fear-inducing headlines about AI keep coming. Are robots indeed coming for our jobs? One study found that 47 percent of all U.S. occupations will be lost to automation within the next 10 to 20 years. There are two crucial caveats to that estimate, though. First, in some ways, the estimate violates the fallacy of composition assumption in economics -- something is true of the whole because it is true of part of the whole. The automation of tasks within the evaluated occupations does not necessarily translate into automation of the occupation itself, in other words. Occupations consist of a bundle of tasks and not all of those tasks may be easily automated. Many occupations that would be considered highly automatable incorporate tasks such as face-to-face interaction, flexibility, judgment and common sense, which are hard to automate. So when you approach the question this way and determine which tasks will be automated, it’s estimated that a much lower percentage of all occupations -- 9 percent -- will be lost to automation.

Secondly, while it is possible to derive estimates of how many jobs will be lost to automation, it is actually impossible to estimate how many new jobs will be created because of it. Smart machines will improve the productivity of labor, but it won’t necessarily displace it so robots will have to coexist with humans. Even as automation has moved from the manufacturing sector into the service sector (see: room-delivery service robots, above), the automation of mundane skills allows employees to refocus on other customer service tasks -- tasks that require higher skills and human interaction.

The fact is that we are currently in only the first stage of AI development, which scientists refer to as the Artificial Narrow Intelligence stage. In this stage, machines specialize in one area -- playing chess, making music selections, translating languages, high-frequency algorithmic trading. Our smartphones are a collection of Artificial Narrow Intelligence. The passage from Artificial Narrow Intelligence to the next stage, Artificial General Intelligence, has proven incredibly challenging. Artificial General Intelligence is when the machines reach and exceed the intelligence level of a single human. The machine would have the ability to think abstractly, reason, comprehend complex ideas and learn from experience.

Source: BBVA Research & Barrat (2013)

Economists have a special interest in the third and final stage of development, known as Artificial Super Intelligence, where the machine would be smarter than all of humanity combined. There’s an economic construct known as Singularity, which is defined as accelerating economic growth due to the rapid growth in the productivity of intelligent machines. It is, in essence, the economist’s perception of how far or close we are from the Artificial Super Intelligence takeover. Noted Yale economist William Nordhaus has formalized seven empirical tests to gauge the viability of Singularity, and it turns out that only two of them yielded positive outcomes. Even so, the extrapolation of estimated trends suggests that the time at which even that could be reached is 100 years or more.

Why so slow? It’s because the productivity gains from the intelligent machines already in existence have yet to materialize and reach the scale where cost-benefit analyses spur private firms to start large-scale development and production. Demand or supply side effects should affect relative prices in such a manner that the substitution of stagnant economic inputs and outputs with high-growth and high-productivity inputs and outputs is feasible. The preferences should move increasingly toward high-productivity, high-growth industries. Production should move toward fast improving digital capital and increasing share of digital capital in the bundle of inputs.

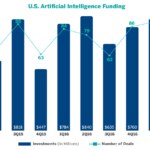

Source: BBVA Research & PwC/CB Insights (2017)

So what should we expect? Not large-scale job losses. Those are unlikely. But at the same time, we should expect large shifts in employment between industries and occupations, as well as adjustments of tasks within occupations. We also should expect a decline in worker hours and a growth in living standards because, so far, that’s the major documented impact of automation on labor. Taking advantage of automation may slowly lower the standard 40-hour work week.

Nurturing the skills of the future -- social intelligence, problem-solving, creativity, coordination, and the ability to cope with the uncertainty of rapidly changing technology -- will greatly affect the country's future

On average, we should not expect wage increases. Automation and information communication technologies put downward pressure on wage growth because of heightened competition for jobs from both machines and offshoring. Also, automation and digitization continue to put downward pressure on the price of capital, as the prospect for digital capital is to grow into a resource that is abundant, has low marginal costs, and is fundamental for all industries.

No matter when we reach the Artificial Super Intelligence stage, the ability of the U.S. to form a long-term human capital investment strategic plan for producing skills that complement rather than substitute smart machines is what matters most. Nurturing those skills of the future -- social intelligence, problem-solving, creativity, coordination, and the ability to cope with the uncertainty of rapidly changing technology -- will greatly affect the future of productivity growth, labor market conditions and wage growth.

Shushanik Papanyan is an economist at BBVA Compass. Her research paper is available online: “When Robots Do It All and Leisure is Mandatory: Not for another 100 years.”

Any statement or opinion of an economist affiliated with BBVA Compass is that economist’s own statement or opinion and does not represent a statement or prediction by BBVA Compass, its parent companies or management.