How to clean up a hot, dark atmosphere

Indian climatologist Veerabhadran Ramanathan decided to study climate change when he realized the full extent of how human activity was altering the composition of our air. It was in the mid-1970s and he had just discovered that carbon dioxide is not the only atmospheric greenhouse gas: there are others called “trace” gases less abundant than CO2 but capable of trapping a thousand times more heat, and their atmospheric concentration is likewise on the rise.

Ramanathan’s finding helped open the eyes of the international community to the gravity and urgency of the climate change challenge. Twenty years later, Ramanathan would obtain another result no less alarming in its implications.

In his first deployment of small unmanned aircraft of the type we now call drones, he came across a vast, dark cloud the size of a continent over the Pacific Ocean. The surprise of its expanse was matched by the surprise of its composition: soot, the contaminant that makes smoke black.

The developed countries were able to reduce – if not eliminate – levels of this pollutant several decades back, but poor countries continue to burn huge quantities of the fuels that produce it. The problem is that soot is toxic, and causes the death of millions of people a year worldwide.

Not only that, Ramanathan discovered that soot exerts a potent greenhouse effect. The vast black cloud over the Pacific yokes together climate change, poverty, pollution and disease. For Ramanathan it also recalled an everyday scene from his childhood in India: his grandmother coughing as she cooked over a dung-burning stove.

Veerabhadran Ramanathan , with traditional Indian cuisine. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego

We could say that Ramanathan, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (San Diego, United States), has specialized in bad news. But the winner in the eighth edition of the BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Awards in the Climate Change category has also used his discoveries as a launch pad for new strategies against climate change. He reckons, for instance, that if we can curb emissions of soot and trace gases as well as reducing those of CO2 , we can cut in half projected global warming over the next thirty-five years.

The bad news is that there are other contaminants besides CO 2 with a massive climate impact; the good news is that by curbing their emissions we can slow down global warming — Ramanathan

The jury acknowledges this facet in citing not only Ramanathan’s science but his proposals “to mitigate climate change in a way that also improves air quality and human health, especially in more impoverished regions of the world.” It also highlights the climatologist’s role as an advisor to political and religious leaders like Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama, and his ability to “communicate the risks posed by climate change and air pollution.”

Born in Madurai, India, in 1944, Veerabhadran Ramanathan trained as an engineer and soon found a job in a refrigerator factory – dealing with the same gases at the center of his first discovery, many years later. The experience failed to enthuse him. He went back to university to complete his education and decided to pursue his doctorate in the United States.

As he was traveling there, the head of his host group at the State University of New York switched to a new line of work, and instead of combustion Ramanathan found himself studying the greenhouse effect on Venus and Mars. The change suited him so well that he ended up at NASA investigating the influence of atmospheric ozone on the Earth’s climate.

And that is how in 1975 Ramanathan discovered that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), gases then solely associated with the destruction of the ozone layer – and used in refrigerators like those in the factory that once employed him – were also powerful drivers of the greenhouse effect. One ton of CFCs traps as much heat in the atmosphere as 10,000 tons of CO2 .

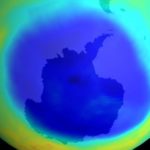

Picture of the Ozone hole over Antarctica. NASA

The science community was initially skeptical: How could gases present in such small quantity alter the atmosphere to that extent? Ramanathan’s sums, however, were correct. Not long after, other trace gases with a powerful greenhouse impact came to light, among them methane and HFCs (precisely the coolants used in place of CFCs because they were harmless to the ozone layer). And now we know that trace gases are to blame for half the greenhouse effect ascribable to human action.

But there is good news too. Carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for centuries, whereas soot and trace gases vanish in relatively little time. Hence Ramanathan’s insistence that we must cut emissions of these short-lived contaminants as well as those of CO2 : “This would bring rapid warming mitigation, delay environmental disaster and give us time we desperately need to radically change our energy diet.”

Ramanathan stresses that climate change is a problem with its origin in the world’s richest countries, but whose burden will fall disproportionately upon the poor: “Three million people who have nothing to protect them, whom we cannot leave to their fate.” With this argument, and the desire to combat the feeling of “total failure” that afflicted him after thirty years producing “one bad-news paper after another,” in 2004 he set up the NGO Project Surya, aimed at replacing India’s traditional stoves – burning fuels that blacken the air and the future – with solar-powered cookers.