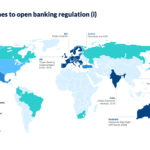

Open banking regulation around the world

Over recent years open banking has become synonymous with the digitalization and transformation of the financial sector. New regulation has been one of the major drivers, starting in Europe before quickly spreading around the world.

Over recent years open banking has become synonymous with the digitalization and transformation of the financial sector. New regulation has been one of the major drivers, starting in Europe before quickly spreading around the world.

There’s no fixed definition, but open banking - and its bigger brother, open finance - typically refer to the liberation of customer data and accounts. In an open banking (or open finance) world, customers can delegate access to their accounts to third parties so that they can read their data or perform operations on their behalf. The access itself takes place through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), software links that allow secure, rapid and dependable communication directly between two firms.

With this, it’s hoped, comes greater innovation and competition. Previously proprietary data is now available for use by new entrants, individuals and firms can leverage their data to seek out better deals, and new services can grow up around an ecosystem of data exchange. In many ways, open banking represents the original ideals of the internet-era: returning control to customers and lowering barriers to entry.

An array of different policy initiatives across jurisdictions have emerged to try to make this a reality, ranging from direct regulatory requirements (such as in the EU, UK, Mexico, Turkey or Australia) to market-coordination (Japan, Hong Kong), guidance (Singapore) and industry-led initiatives (New Zealand, Colombia).

It’s not just the style of intervention that differs, but also the scope, with substantial variations across:

- which entities and products they apply to - just banks, or other types of financial entities;

- what information should be accessible by third parties, with the customer’s consent - such as transactional information, product data, or aggregated statistics; and

- whether operations, like account-to-account payments or contracting new products, are included.

Just as importantly for many third parties, the initiatives also have different approaches to standardisation - the degree to which data formats, security rules (like customer authentication), API frameworks, and elements of the user experience are common across entities. Standardisation makes life easier for third parties and can ensure minimum requirements are met, but also risks increasing costs and reducing flexibility.

These are some of the initiatives with different approaches:

- Europe: The revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) in Europe applies to banks and e-money providers and facilitates access for third parties to both transactional data and to payment operations. Banks can choose whether to develop APIs which, although not standardised, must be approved by authorities. Industry groups such as The Berlin Group have developed their own API standards to support implementation.

- Mexico: The Fintech Law in Mexico on the other hand applies to almost all types of financial entities and both transactional and product data, but it doesn’t include payment operations. Common API standards are being developed by the authorities.

- Australia: The Consumer Data Right in Australia applies only to banks (although eventually will also include other sectors of the economy, such as energy and telecoms). It includes transactional and product data across a wide range of product types, with standardised APIs.

Growing pains

These varying styles of open banking policies have helped to illuminate some of the challenges and inconsistencies in the emerging frameworks. First, while everyone agrees that financial data is highly sensitive, not all initiatives have yet put in place adequate controls regarding which firms can act as third parties to access data on behalf of a customer.

Second, even where controls are in place, clear rules on liability and dispute resolution are missing which would ensure that if a problem does occur it's clear how the different entities involved should resolve it.

Third, not all frameworks have been designed with their sustainability in mind. While in some jurisdictions firms are allowed to charge a nominal fee to third parties to cover the costs of providing API infrastructure, in others, such as PSD2 in Europe, any charging of this nature is prohibited.

Implications for the financial sector

More challenging questions are also starting to be asked about the possible impact of open banking on competition and the structure of the financial sector in the medium term.

While open banking means that customers can easily share their financial data, no jurisdictions currently ensure that customers can do the same with data held in other sectors. As boundaries blur in the digital environment, non-financial firms could leverage open banking to access new financial data, giving them an unfair advantage over financial sector players who aren’t competing on the same terms.

In addition, policymakers have recognised that by accelerating structural changes and amplifying existing risks related to BigTech’s inroads into financial services, open banking could have a detrimental impact on financial stability. The Financial Stability Board, for example, has highlighted that it could reduce the “stickiness” of bank deposits.

The adoption of open banking regulatory initiatives is likely to continue in the future, as more jurisdictions look for ways to support competition and innovation, as well perhaps as ways to encourage digitalization in response to the Coronavirus crisis. To ensure the promised benefits materialise while also managing new risks, we need to learn from the experiences to date and design broader frameworks that work across sectors and account for the impact of policies on the structure of markets.